JIPS’ Support in Mexico on Capacity Building for Improved Displacement Data (Nov 2019)

Internal displacement has been present in Mexico for decades and diverse actors have been responding to the phenomenon in different ways. However, it was only recently, in April 2019, that the Mexican government officially recognised internal displacement. The meetings we organised and facilitated during our recent scoping mission to the country were actually the first time that these different actors – national and local-level government actors, civil society organisations, academia and the international community – all came together around the same table, to discuss how to jointly shape a coherent and shared approach.

The scoping mission is part of the support JIPS is providing to stakeholders in Mexico, aimed to inform a national strategy for building critical capacities among actors involved in the response to internal displacement and related quantitative and qualitative research work. Partners include:

- Federal government entities under the Ministry of the Interior (SEGOB): Unidad de Política Migratoria Registro e Identidad de Personas (UPMRIP), the Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR), Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO), and the Comisión para el Diálogo con los Pueblos Indígenas de México (CDPIM),

- Civil society represented by the Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos (CMDPDH),

- The international community including UNHCR, OCHA, and OHCHR, and

- State government actors, including Secretaria de Protección Civil de Chiapas and the Comisión Ejecutiva de Atención a Víctimas del Estado de Chihuahua (CEAVE).

Jessica Lopez introducing the final debriefing session at SEGOB’s Benito Juarez venue.

During the three weeks in Mexico, our colleagues, Dr. Isis Núñez Ferrera, Head of field support and capacity building, and Andrés Lizcano Rodríguez, Profiling advisor, organised and facilitated a series of discussions and working sessions with stakeholders at national, local and international level. Partners jointly elaborated seven recommendations to build and strengthen critical capabilities. Read on to learn more from the mission, the current information landscape in Mexico, and the resulting recommendations.

Internal displacement in Mexico, legal processes, and information landscape

According to the CMDPDH, every year tens of thousands of people are internally displaced in Mexico. Violations of human rights but also generalised violence and disasters are known to be main drivers of these displacements.

Study “Violence as a cause of forced internal displacement” by the National Population Council (CONAPO) and the Ministry of the Interior (SEGOB).

The phenomenon has been documented at least since 1972 and systematically monitored by the CMDPDH since 2014 (see its annual reports). However, it was only in April 2019 that internal displacement received official recognition with the publication of the study “Violence as a cause of forced internal displacement” by the National Population Council (CONAPO) and the Ministry of the Interior (SEGOB).

Efforts to introduce a legal framework at federal level date back to 1998, and are now materialising with an IDP bill that is being prepared by the government to provide a normative basis for its response to internal displacement. Two out of the 32 Mexican States – Chiapas and Guerrero – already have IDP laws in place, and Chiapas’ state authorities are currently working to operationalise the law. The state government of Chihuahua is elaborating a protocol for IDP assistance. UNHCR has been supporting the processes in Chiapas and at the federal level, and is standing by to provide broader support as requested by the government.

The CMDPDH’s annual reports and other publications on internal displacement, now complemented by CONAPO’s review of surveys and by its report on profiles of displaced populations, add to a body of evidence that furthermore includes academic work, an in-depth report by the National Commission on Human Rights (2016), and ad-hoc documentation of cases and registries of individual displaced communities. However, currently available information is neither comprehensive, nor displacement-specific, institutionalised, or representative of the country. Furthermore, these efforts are often isolated and reactive, and there is no common framework. Partners in-country therefore realised the need for building adequate capacities and skills to produce, analyse, and use information on internally displaced people more systematically and for longer-term strategies and solutions.

The request for JIPS’ support occurs a year and a half after the unofficial visit to Chihuahua of the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of IDPs, Cecilia Jimenez-Damary, and at a moment when OCHA and UNHCR have agreed to support the government response. It also aligns with the governments’ recent engagement with IDMC, who has been using the CMDPDH’s figures for its Global Report on Internal Displacement, and with the involvement of Mexico’s National Office on Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI) in the Expert Group on Refugee and IDP Statistics (EGRIS).

The collaborative nature of the mission and the activities planned in partnership with the government, civil society and UN partners contributed to an inclusive and neutral space to engage on technical and often complex discussions related to data on internal displacement.

Observations on data systems and approaches at federal and state levels

It became clear from the discussions and meetings during our scoping mission in Mexico City as well as in Chiapas and Chihuahua, that numerous challenges persisted when it comes to data on internal displacement in Mexico:

- General awareness of internal displacement: although institutional roles are currently being clarified through the new IDP bill, many government agencies are not yet involved. There is also a lack of a common understanding of the phenomenon as well as related definitions and frameworks, such as the IASC Framework on Durable Solutions for IDPs, that would allow to analyse collected data in a coherent manner.

- Ad-hoc approaches: current approaches to generating and managing data are mostly ad-hoc and focus on informing (short-term) humanitarian assistance and protection. This results in data that is often limited in use and that isn’t fit-for-purpose to inform longer-term solutions despite the often-protracted nature of displacement.

- Information landscape: several data systems exist at national and state levels. Some of them have been in place since long before the official recognition of internal displacement in Mexico in 2019. Nevertheless, these systems aren’t systematically maintained or coordinated, nor interoperable or shared. There is also a National Register of Victims; however, disagreement about roles, scope, and legal concerns have led to victims of displacement not to be included here. In the absence of a comprehensive and shared evidence base on the scope and impact of internal displacement, official statistics are used as a proxy. Nevertheless, these statistics are based on surveys that have not been designed to gather information about internal displacement.

Oscar Coronel Palacios from the National Civil Protection Coordination Office explains how they gather information before providing humanitarian assistance.

State of Chiapas

Chiapas has very diverse situations of displacement, including due to land disputes, religious reasons, community expulsion, and the 1994 Zapatista uprisings. It is one of the two Mexican States with a law on internal displacement and it has a state-level council to help in assisting displaced populations. Several information systems are in place (the database of the Consejo Estatal de Atención Integral al Desplazamiento Interno, the State’s Civil Protection System, censuses carried out by the Secretary of Health as well as communities themselves) allowing for a rich evidence base. Similar to the national level, key challenges are linked to the council’s primary focus on humanitarian aid and the lack of a shared analysis as well as interoperability between existing information systems.

State of Chihuahua

High-level support from the State Government has allowed for an ad-hoc response to internal displacement despite the absence of a relevant legal framework. This has included monitoring of IDP assistance using an alternative registry, developing a baseline study and carrying out contextual analysis based on documented cases. Whilst efforts by the government are underway to systematise the approach and implement more adequate primary data collection, current focus remains exclusively on humanitarian needs with a lack of long-term planning processes and adequate analysis that can inform these.

Participants discuss internal displacement cases and available evidence during our workshop in Chihuahua.

Looking Ahead

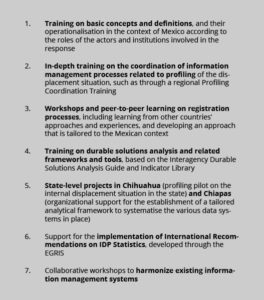

Seven recommendations resulted from JIPS’ mission in November 2019.

Building on the discussions and working sessions held during our three-week scoping mission, we elaborated a set of seven recommendations (see info box). These were presented to, and welcomed by the high-level representatives of the different institutions and organisations during our final debrief session. Partners in-country are currently working on prioritising the recommendations, not all of which will be implemented in 2020, as well as elaborating a concrete timeline and action plan.

Importantly, we put particular emphasis on strengthening the collaboration between the different actors working to address internal displacement, including government, civil society, academia, and the international community. Experience shows that this collaboration is essential for effective and coordinated information management systems on internal displacement, and ultimately for adequate responses towards longer-term solutions. JIPS looks forward to supporting partners in the implementation of these activities.